When I gave up smoking four years ago, it struck me how important smoking had been to my experience of travelling: I no longer had any idea how much time to spend staring at a beautiful view or taking in an atmospheric street scene. One minute? An hour? Ten seconds? It used to be measured in cigarettes. The rapid expansion of coffee culture in the English-speaking world in the 21st century—both of the branded, Starbucks variety, and its hipster, Australasian cousin—can partly be understood as plugging this gap. A dose of caffeine takes longer to administer than one of nicotine, but both provide a staging post, either solitary or social, in a day that is otherwise short of routine.

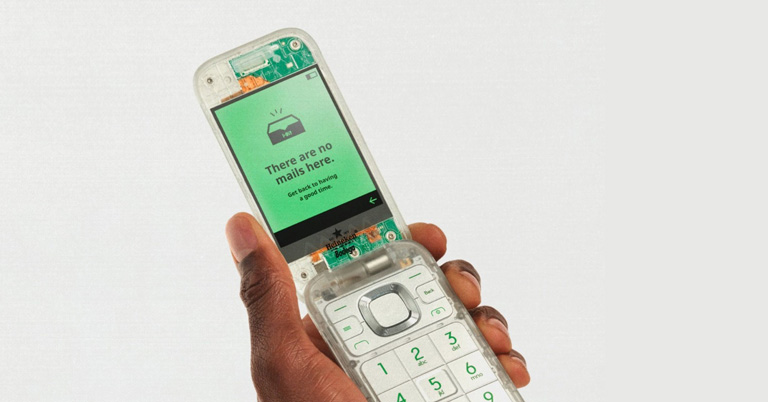

I once asked an old friend, through a thick haze of smoke, what he liked most about a cigarette, to which he replied, “It frames a moment.” In the age of the smartphone, we have developed a more literal way of framing moments: a digital record is made, always with the possibility of being shared. The selfie is the more infamous manifestation of this, putting the taker’s narcissism on full public display. Yet this is simply a more brazen version of the banal tweet or status update about one’s whereabouts or activity.

In the aftermath of smoking, the smartphone has become our handy “moment-framing” tool of choice, even more so than the coffee cup. As with the cigarette, the smartphone feels most needed at precisely those moments when routine is most lacking, like when we’re between other places or waiting for someone to arrive. The strange need to inform one’s friends and followers that one is presently in an airport (tweets such as “JFK>LHR”) speaks of a latent desire for framing that might once have been sated by a cigarette. It’s not as if air travel is remotely exotic or exciting any longer, but more that it creates a sense of “between-ness” that prompts the urge for an anchor.

In a superficial sense, the smartphone is quite a good cigarette replacement, and certainly a less carcinogenic one. It offers us something to do with our hands, and a way of feeling legitimately alone in public spaces like cafes. It fits into the pocket. For some people, it’s the first personal item that they reach for after a meal or after sex, just like a cigarette (the challenge with smart phones is to resist looking at them during these activities). Adults need objects that travel around with them, confirming their identities from place to place, not unlike children. If I can no longer smoke a ‘fag’ (as we like to say in Britain) as I gaze at the sun setting over a harbor, I can at least snap the moment on my phone, with or without a selfie stick.

But on a deeper psychological and cultural level, the difference between these two framing devices could scarcely be more profound. This touches on the malaise of anxiety that has become the dominant psychiatric disorder of our age. While smoking affirms the limits of time and space around us, smart phones do precisely the opposite. While one allows you to spend a finite chunk of time in a given space, as a break from the flux of work or travel, the other connects you to a more complex and fluid world beyond your immediate situation.

As framing devices go, the smart phone suffers from the inherent problem that it is leaky. It is constantly connecting us to other times, other places, absent people, absent places, some in the future and some in the past. The selfie may seem narcissistic, but it is captured with the possibility of being seen by others who are not present (at least, not yet). If it is an expression of anything, it is one of paranoia: paranoia that human memory is no longer adequate for experiences, that one may be seen by others, that one may not be seen by others.

This is a restless condition. Where the cigarette allows us to (in the immortal words of Oasis’s horrifically bombastic 1997 album) be here now, a smart phone allows us to do precisely the opposite. In this psychological sense, it is the very antithesis of a cigarette. The transition from the one object in our pocket to the other speaks of a more general shift in the character of capitalism.

The rise and fall of smoking closely mirrors the rise and fall of another notorious pollutant: industrial manufacturing. Smoking levels and industrial jobs in the United States and United Kingdom both peaked just after the Second World War, when over 80% of adult men were smokers, and close to 40% of employment was in manufacturing. These rates are now at around 18% and 10% respectively, and falling.

Besides both puffing out smoke, factories and cigarettes shared a common economic culture, based around stable, mechanical routines. This is equally true of traditional white collar, professional jobs in the pre-digital age. Smoking, to the extent that it is still tolerated today, reflects some of the values of the mid-20th century workplace. Smoking breaks happen with a certain regularity, lasting the three or four minutes it takes to finish a cigarette. The workplace ‘smoking room’ was traditionally the place where colleagues would have a brief conversation with others, regardless of hierarchy, safe in the knowledge that it could only last a few minutes and would then be largely forgotten about.

It is generally taboo to point out the psychological security provided by smoking. One exception is where mental health patients are concerned. In 2013, Britain’s health regulator, NICE, demanded that hospitals ban patients from smoking outside. Given that over 80% of diagnosed schizophrenics are smokers, this alarmed some mental health experts and charities, who argued that some patients’ lives would clearly be worse without cigarettes. Mightn’t there be other less serious cases, anxiety-sufferers for example, who would also benefit from a more forgiving view of this habit?

Smoking’s decline has gone hand in hand with the decline of predictable working and leisure routines. In place of the rhythm of work, break, work, break, which cigarettes helped to punctuate, we now live in a society that lacks interruptions. This shift was noted in a short but influential essay by French philosopher Gilles Deleuze. In “Postscript on Societies of Control,” Deleuze contrasted what he termed “control societies” of the late 20th century with the “disciplinary societies” that emerged in the 19th century. As Deleuze argued, “In the disciplinary societies one was always starting again (from school to the barracks, from the barracks to the factory), while in the societies of control one is never finished with anything.”

Contemporary society, as Deleuze noted presciently, lacks adequate boundaries between one period in time and another. It lacks ways of “framing a moment.” Hence, in our relentless celebration of the decline of smoking, we are also accelerating the demise of “disciplinary” or “industrial” routines which while inflexible and unhealthy, once provided an amount of psychological security.

For the flexible, enterprising, gym-going success stories of our always-on age, this is a win-win. For those at the higher end of the labor market, physical health and economic productivity are now a single virtue to be pursued at all times. But it turns out that many people cannot cope with this uninterrupted stream of experiences, data and movement. The condition of being “never finished with anything” is at the root of a pervasive disquiet.

It’s in this context that we can understand the rise of “mindfulness” as a tool of managers in the workplace. It has recently been suggested by British politicians that “mindfulness” should be taught to government employees, as a way of dealing with stress and anxiety, which lead to absence from work and costs to the taxpayer. Techniques for aiding concentration, such as meditation or “digital detoxing,” are now central parts of the armory of management and life coaching, even becoming compulsory in some workplaces.

While mindfulness may claim a Buddhist lineage dating back over 2,000 years, its present popularity is primarily explicable in terms of contemporary economic culture and technology. The goal of mindfulness is to dwell entirely in the moment, simply noticing one’s own thoughts, body, and environment. It is a way of punctuating the constant flow, giving the self a brief, circumscribed period when thoughts and feelings can simply be observed, without concern or judgment. It frames a moment in time. Come to think of it, it sounds very like stepping outside for a cigarette.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote that “civilization is a hopeless race to discover remedies for the evils it produces.” Now that wellbeing gurus exhort us to monitor our rest and relaxation, to ensure that we’re taking an optimal amount of time away from work and screens, the particular evil of post-industrial capitalism is abundantly clear. In the quest for a more flexible, healthy, seamless capitalism, we’ve lost the ability to be in one place at one time, or one conversation at one time. Anxiety is the inevitable result.

But the remedies are simply inversions of the problem. In response to the paranoid condition of hyper-connectivity, we are offered a complete, silent insularity. The digital age is gobbling up the convivial middle ground between connection and disconnection – the sort of middle ground represented by the smoking room. Why must we be trained how to sit motionless, alone with our thoughts? Why not chat idly to one’s colleagues for ten minutes, or go for a walk? One reason why not is that, unless one is a smoker, these exercises do not simply just happen any longer.

It would be perverse to wish for a return to a 1940s society of smokestacks and cigarettes. But it is stupid to think that we can simply train ourselves into a state of calm, against the countervailing forces posed by business, policy, and digital technology. Against the ideals of limitless health and limitless connectivity, we need to defend the right to separate our lives into different times and places, some of activity, others of passivity, some of conversation, others of solitude. We shouldn’t need Buddhism to articulate this. And if it involves the occasional cigarette, so be it.

Source: opendemocracy.net : Author: William Davies

![Best Gaming Laptops in Nepal 2024 [Updated] Best Gaming Laptops in Nepal 2023 - June Update](https://cdn.gadgetbytenepal.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Best-Gaming-Laptops-in-Nepal-2023-June-Update.jpg)

![Best Mobile Phones Under Rs. 15,000 in Nepal [Updated] Best Phones Under 15000 in Nepal 2024 Budget Smartphones Cheap Affordable](https://cdn.gadgetbytenepal.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Best-Phones-Under-15000-in-Nepal-2024.jpg)

![Best Mobile Phones Under Rs. 20,000 in Nepal [Updated] Best Mobile Phones Under NPR 20000 in Nepal 2023 Updated Samsung Xiaomi Redmi POCO Realme Narzo Benco](https://cdn.gadgetbytenepal.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Best-Phones-Under-20000-in-Nepal-2024.jpg)

![Best Mobile Phones Under Rs. 30,000 in Nepal [Updated]](https://cdn.gadgetbytenepal.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Best-Phones-Under-30000-in-Nepal-2024.jpg)

![Best Mobile Phones Under Rs. 40,000 in Nepal [Updated] Best Phones Under 40000 in Nepal 2024 Smartphones Mobile Midrange](https://cdn.gadgetbytenepal.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Best-Phones-Under-40000-in-Nepal-2024.jpg)

![Best Mobile Phones Under Rs. 50,000 in Nepal [Updated] Best Phones Under 50000 in Nepal 2024 Smartphones Midrange](https://cdn.gadgetbytenepal.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Best-Phones-Under-50000-in-Nepal-2024.jpg)

![Best Flagship Smartphones To Buy In Nepal [Updated] Best Smartphones in Nepal 2024 Flagship Premium Samsung Apple iPhone Xiaomi OnePlus Honor](https://cdn.gadgetbytenepal.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Best-Smartphones-in-Nepal-2024.jpg)