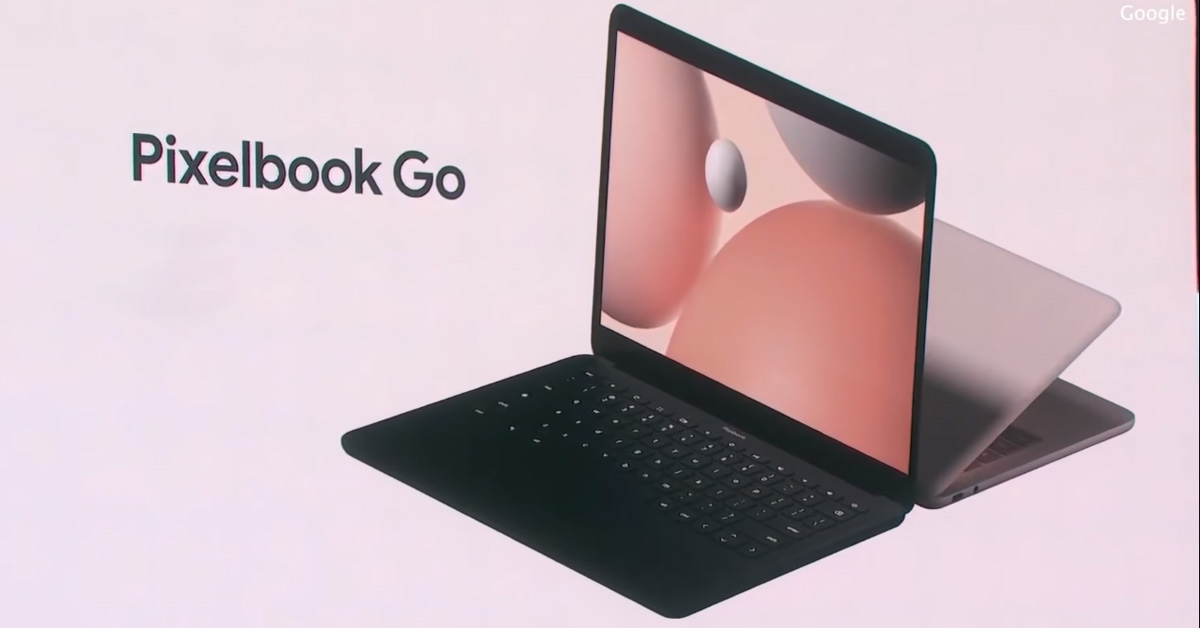

Google's newest Chromebook - the Pixelbook Go is now official. The company unveiled the device on its "Made by Google '19" event alongside other products. The Pixelbook Go is an affordable iteration to the original Pixelbook from 2017. But does the affordability justify its worth and will it hold out against the competition? Let's find out!

Furthermore, $999 gets you the same Pixelbook Go with the i5 processor with 16GB of RAM. The top-tier variant has 8th Gen Intel Core i7 processor, 16GB RAM, 256GB storage, and a 4K UHD display. Unlike the predecessor, there's no NVMe SSD storage option.

Also read: Google Pixel 4 & Pixel 4XL launched!

Similarly, the Pixelbook Go's Chrome OS hasn't nearly been around as long as Microsoft's Windows OS has. From the familiar UI to app support, the superiority of the latter is astounding. However, Chromebooks have come a long way since the days of supporting only web applications. Chromebooks support Packaged Apps (Chrome Apps), a select arsenal of Android apps and since 2018, Linux apps too.

Furthermore, $999 gets you the same Pixelbook Go with the i5 processor with 16GB of RAM. The top-tier variant has 8th Gen Intel Core i7 processor, 16GB RAM, 256GB storage, and a 4K UHD display. Unlike the predecessor, there's no NVMe SSD storage option.

Also read: Google Pixel 4 & Pixel 4XL launched!

Similarly, the Pixelbook Go's Chrome OS hasn't nearly been around as long as Microsoft's Windows OS has. From the familiar UI to app support, the superiority of the latter is astounding. However, Chromebooks have come a long way since the days of supporting only web applications. Chromebooks support Packaged Apps (Chrome Apps), a select arsenal of Android apps and since 2018, Linux apps too.

Google Pixelbook Go

Thin, light, and fast - for a price. Credit where credit is due; the Pixelbook Go is a welcome upgrade to its predecessor. Sporting a bigger 13.3-inch touchscreen display with a 15% larger battery, while simultaneously weighing less than the original Pixelbook is an amazing feat achieved by the company. The Pixelbook Go now comes in a magnesium chassis to Pixelbook's aluminum with Grippable finish on the bottom making it easier to hold and carry. On a related note, it ditches the 360° hinge mechanism of the former Pixelbook and feels more like a premium laptop rather than a convertible. Affordability is another hurdle that Google hopes to kinda-sorta pass through with the Pixelbook Go. The base model starts at $649 which is less than the asking price for the base model of Pixelbook but admittedly, is still expensive than Chromebooks by other manufacturers like Acer, Asus, Dell, HP, and Samsung. You get to choose between 4 models of the Pixelbook Go with varying processors, display quality, and memory configurations. Okay, so what's the catch here? Performance level, of course. The cheapest variant is equipped with an 8th Gen Intel Core m3, 8GB of RAM, and a meager 64GB of SSD storage which cannot be further expanded using a microSD card. Bummer! Google really skimped on storage options this year. The Core m3 is a fairly powerful chip considering it's a Chromebook, but I'd rather have an i5 or an i7. For $200 more, you can get the Pixelbook Go with 8th Gen Intel Core i5 and an upgraded 128GB storage.Google Pixelbook Go Specifications

| Google Pixelbook Go | |

| Body | 12.2 x 8.1 x 0.5-inch; 1.061 kg |

| Display | 13.3-inch LCD touchscreen panel |

| Resolution | Full-HD Display (1920 x 1080) / 4K Ultra-HD Molecular Display (3840 x 2160); 16:9 aspect ratio |

| Battery | 47-Watt hour (FHD panel) / 56-Watt hour (4K UHD panel); Up to 12 hours of usage in a single charge |

| Processor | 8th Gen Intel Core m3 / i5 / i7 |

| RAM | 8 / 16GB |

| Storage | 64 / 128 / 256GB SSD |

| Audio | Dual front-firing speakers; 2mics for noise cancellation |

| Security | Titan C security chip; Built-in FIDO authenticator |

| Camera | Duo Cam; 2MP f/2.0 aperture |

| Keyboard | Full size with 19mm pitch; Hush Keys, Google Assistant Key; Backlit |

| Ports | 2 USB-C charging and display output; 3.5mm headphone jack |

| Connectivity | Wi-Fi: 802.11 a/b/g/n/ac, 2x2 (MIMO), dual-band (2.4 GHz, 5.0 GHz); Bluetooth 4.2 |

| Colors | Just Black, Not Pink |

| Price | $649 / $849 / $999 / $1,399 |

So who is the Pixelbook Go really for?

On an obvious note, the Google Pixelbook Go isn't for the most hardcore users who need to run the most intricate of software or play AAA title games. Chances are, Pixelbook Go doesn't even support those high-end softwares and AAA games. The Pixelbook Go is perfect for those looking for simple low-end computing, web browsing, and media consumption on an ultra-thin, beautiful, lightweight, and power-efficient build. If you're embedded into Google's ecosystem and its products, the Pixelbook Go is the way to go.Google Pixelbook Go vs the options

A quid pro quo! As mentioned earlier, there are tons of other Chromebooks or Windows laptops you could go for instead of the Pixelbook Go. Consequently, there will be some trade-offs in either of the options. The Pixelbook Go will give you a clean UI, advance security through its Titan C chip, a quieter "Hush" keyboard, and an all-day battery. On the contrary, other Chromebooks can give you 360° flip for tablet mode, a better value for your investment, so on and so forth. Similarly, a Windows machine will give you more power and versatility at a similar cost. For instance, you could get the Asus Chromebook Flip (C302CA) which has similar specs at a lower price than the base model of the Pixelbook Go. Comparatively, the Dell XPS 13 or the recently launched Surface Laptop 3 proves to be a better and more powerful machine, though unescorted by the Pixelbook Go's battery performance.Article Last updated: October 17, 2019

.gif)